RightsCon is the world’s leading event on human rights in the digital age. The 2019 edition, taking place this week in Tunis, brings together 2500 participants from 130 countries (NGOs, governments, companies). Etalab has been selected to lead a session about algorithmic accountability.

« With great power comes great responsibility »

On this occasion, Etalab is publishing a working paper « With great power comes great responsibility: keeping public sector algorithms accountable » to present our work on algorithmic accountability and to engage the discussion with international actors (NGOs, governments and companies). Here is a short summary of our findings.

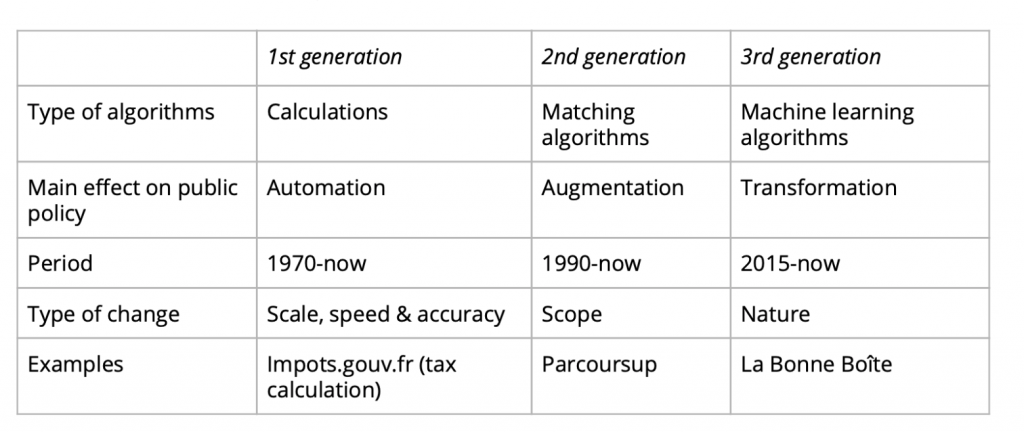

From automation of human tasks to machine learning: a short history of public sector algorithms

Algorithms are nothing new for the public service. In the 1970’s, the emergence of the computing industry allowed the French authorities to automate some of its administrative processes, starting with the large-scale processes, like tax and social benefits calculations. The second generation started with the use of matching algorithms, mainly for human resources management. The Ministry of Education developed a system to manage their workforce, that is, educators and teachers applying for a new position in a different school or region. Since the early 2000’s, matching algorithms have been used for student allocation such as Affelnet, Admission Post-Bac, and now Parcoursup. The third generation of public sector algorithms is linked to the emergence of machine learning (ML) algorithms which represent a major shift for public policy. In the first two periods, computers were used to apply a set of rules that were sometimes complex, but always predefined. Instead, ML algorithms derive rules from observations and learning from large datasets. These systems are used for tax fraud detection, prediction of companies likely to hire (La Bonne Boite) or that present a risk of going bankrupt (Signaux Faibles).

Specific challenges for public sector algorithms

Private and public sectors share a series of challenges (opacity, loss of autonomy, low level of explainability, risk of bias, …) but the latter are distinguable in three ways worth noting.

First, they must be used in the public interest and not a particular or private interest. One can question the impact of YouTube’s recommendation algorithm on the diffusion of harmful content. That said, it is generally accepted that, as a private company, YouTube is pursuing its own interest and not the public interest. Second, in many cases, public sector algorithms tend to implement legal rules. Tax calculations follow a list of rules defined by the general tax law and adopted by the Parliament. As such, some PSA are the last link from the political will to tangible effects on individuals.

Finally, public sector algorithms tend to be unavoidable: citizens do not have the option to use a different algorithm and sometimes are not presented with the choice to opt out of using an algorithm at all. For example, a French patient in need of a heart transplant has no choice but to accept the rules and their algorithmic implementation by the Biomedicine agency. Similarly, the only way to get access to most of the higher education institutions is to go through Parcoursup, the allocation system for students, which relies on an algorithm.

In 1789, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (article XV) stated that “Society has the right to require of every public agent an account of their administration”. This principle, enacted well before the invention of computers, still stands: if administrations use algorithms as tools of administration and government, then they – and their algorithms – should be held accountable.

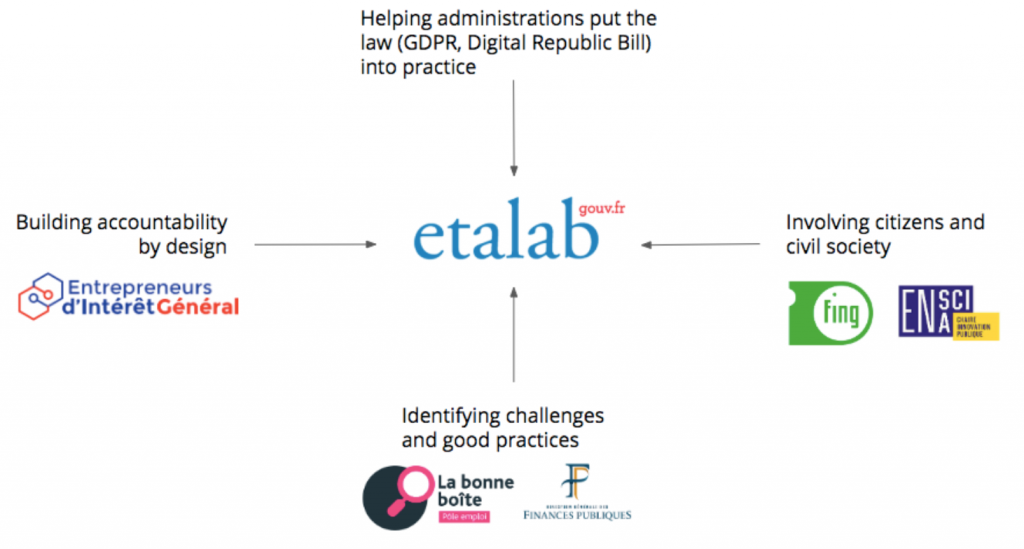

How Etalab is working towards sector algorithms accountability

With the introduction of a new legal framework for algorithmic accountability and transparency (introduced by the Digital Republic Bill), public agencies need to be accompanied on making existing and future algorithms compliant with the new obligations. This also gives citizens access to new rights, such as an extended right to information.

Through the National Action Plan (2018-2020) for the Open Government Partnership, France has committed to reinforcing “the transparency of public sector algorithms and source codes”. Etalab, as the government’s task force for open data and data policy, oversees the work on this commitment which lies at the crossroads between open data, open source, and open government issues.

Our approach is multifaceted:

- top-down: from the general principles and legal obligations to their concrete implementations;

- bottom-up: deriving challenges and good practices from specific case studies;

- inspired by inputs: from external partners and from alternative methods;

- next to: supporting teams developing new algorithms.

To answer to the agencies’ primary need we published a how-to guide on algorithms for public sector agencies. The guide, available online (in French) – open to contributions on GitHub – gives a brief overview of issues surrounding PSA and puts the European and national legal obligations into layman’s terms to make them more accessible to public servants

An investigation method for algorithms

To identify challenges and good practices already in place, we adopted a case-based approach, working with voluntary public sector agencies on existing algorithms. Three different methodologies have been used, each one focusing on a particular object on different domains (namely social services, employment and health):

- observing people at work, and their interactions with algorithmic systems (allocating daycare places at a municipal level);

- observing code being published, and interviewing developers about their choices (helping the unemployed target potential employers);

- observing legal and practical documentation about administrative procedures using algorithms (allocating heart transplants at a national level).

Building accountability by design

In addition to working with existing use cases, we explore accountability by design by working in close collaboration with different organizations and actors. As the department for data policy, Etalab encourages the development of datascience into government through different innovation programs developing rule-based and machine learning algorithms, such as digital transformation program Entrepreneurs d’Intérêt Général and a call for projects around artificial intelligence. We make sure that PSA accountability issues are addressed from the beginning of these programs by organizing workshops and discussions with the development teams (public servants, data scientists, and developers). We work on different topics such as impact, explanation, data bias or symmetry of information.

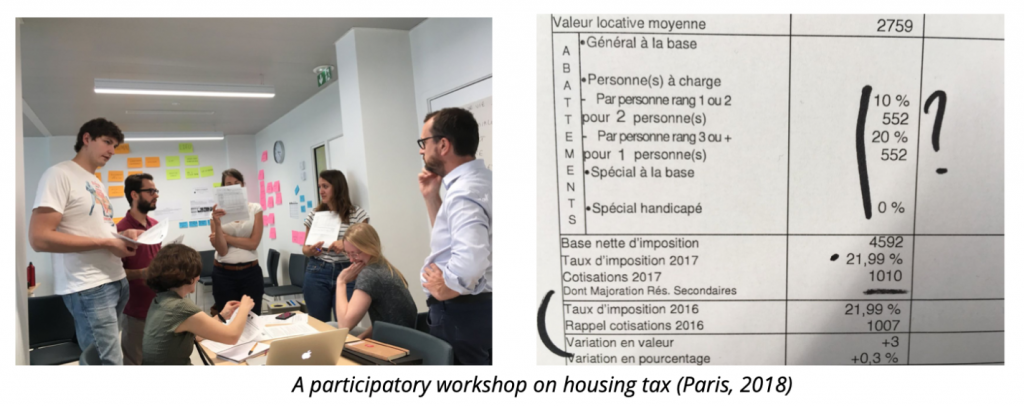

A design workshop to involve citizens

To experiment with involving citizens in making PSA accountable we conducted two participatory workshops on the French housing tax, with the help of PhD candidate Loup Cellard (Warwick University). We used the analogy of an algorithm as a cooking recipe, with ingredients (data), step-by-step preparation methods (instructions) and a final result (amount to be paid).

Getting the participants’ input on how to better explain the tax calculations was important but the workshop was particularly useful for raising awareness around citizens’ right to information with regards to public sector algorithms.

Perspective: public sector accountability and citizens

So far, our department’s missions have been mainly focused on making sure public agencies meet their legal obligations. However, these obligations only make sense if they genuinely enable citizens to exert their rights, and if they result in a juster way to conduct public action.

This raises crucial questions we want to keep exploring: who from outside the public sector should be involved in public sector algorithm accountability and at which step of the process? Secondly, where can and should citizens play a role? How can they help avoid the pitfall of “accountability-washing” and focus the discussion beyond the algorithm and on the public policies at stake? These questions call for broader reflection at two levels: first, nationally, by mobilizing civil society organizations, the media, human and digital rights NGOs, and research institutions while taking into consideration the local social, political and legal contexts. Secondly, through international collaborations with governments and organizations that have been working on these topics.